I originally wrote this meditation on fund evaluation for my quarterly letter to investors, but thought I’d share it more broadly because people frequently ask me about my selection criteria. Hope this helps:

Q3 2017 Commentary:

About a decade ago, a Bay Area billboard campaign for Diet Coke captured the ebullient can-do zeitgeist of the start-up world: “you moved to San Francisco with a crowd-funded website, dad-funded hatchback, and a no-funded bank account. You’re on!”

And indeed, a fundamental change in entrepreneurial finance underpinned this exuberance: while start-ups in the ‘90s typically needed to invest heavily in equipment, development, and customer acquisition just to get off the ground, advancements in virtual infrastructure, open source computing, and go-to market strategies enabled founders to launch companies in a lightweight way. Now able to scale in response to growth, rather than in advance of it, start-ups became radically more capital efficient. By some estimates, the amount of cash needed to get a company to first revenue had come down significantly, from the millions of dollars to the tens of thousands. “Fail fast, fail cheap” became a rallying cry as some joked that the cost to build a company approached the opportunity cost of unemployment.

A thousand flowers of optionality bloomed. Start-ups today are much more substantial businesses and continue to pioneer new industries while increasingly reshaping traditional ones. But this mass flourishing came with a cost: barriers to entry declined significantly and fast followers could now catch first movers quickly. Competitive intensity exploded as many “me too” companies abounded.

To be sure, the VC fund business was not immune to such dynamics. Outsourced service providers eased the administration of funds, fundraising friction decreased, and new platforms offered streamlined the fund formation process. An explosion in activity followed. For example, the so-called Micro VC segment saw the biggest growth in action. Pioneered by a handful of funds, the segment now encompasses over 450 such vehicles. In a typical week, our team will interact with a half dozen or more new teams. Unique ideas rarely stay that way for long; we joke that the time from “frontier technology” to mainstream is a couple of years today. Artificial Intelligence, for example, was a bleeding edge concept a few scant years ago but this fall alone we have seen almost a dozen AI-oriented funds cross our transom.

Unfortunately, the number of great deals is finite and the odds are stacked against new entrants. Yet intelligent and accomplished individuals continue to enter the field. Every aspiring VC seems to have a great story and one LP friend of our recently complained about being snowblind with opportunity. So how do we navigate through this whiteout? Some timeless touchstones guide our evaluation of VCs: outstanding ability, investing sensibility, repeatability, and authenticity.

The first criterion, outstanding ability, serves as table stakes in our discussions with potential new managers. Of all the common forms of investing, VC has historically experienced the widest spread between top managers and mediocre ones. VCs often serve as venture catalysts and their close engagement with companies requires that they have profound domain expertise to evaluate cutting edge companies and help them grow. In a world of competent practitioners, standouts need unfair advantage.

Our second standard, investing sensibility, is one that trips up many managers. The shiny newness of startups can be intoxicating and we see people frequently fall in love with companies, no matter what the price. As fervent believers in Buffet’s Equation, which observes that Opportunity = Value – Perception, we tend to be cynical about momentum plays. Silicon Valley’s spectacular self-promotion engine often allows valuation to outstrip medium-term promise in buzz-y companies. It is very common today to see start-ups attain valuations that assume perfect execution for the coming two years. But ultimately, some final buyer – whether an acquirer or a initial public offering investor – is most likely going to pay a price that has grounding in fundamentals, not hype.

Portfolio construction is another aspect of investing sensibility that can be overlooked. Many aspiring VCs have enjoyed entrepreneurial success. While some of their skills translate well to investing, especially company-building acumen and founder empathy, we have found that many fail to understand how to deploy capital in ways that generate attractive risk-adjusted returns at a portfolio level. Like a casino that rewards the senses with flashing lights and bells, Silicon Valley offers endorphin jolts that do not always correspond with investing success. Frequently, we will see fund managers crow about a win or two that might return some portion of a fund’s capital, but perhaps because of investment craft errors, these winners will fail to lift a fund high enough to overcome all the weak outcomes. Indeed, this is an area to which we devote considerable time mentoring VCs.

For us, the third criterion, repeatability, is also a critical factor. In a business with a poor signal-to-noise ratio, it can be extremely difficult to differentiate between the merely lucky and the truly skilled. Today, it seems that many fund managers are playing the odds, trying to hit it big with the next Facebook or Uber. Indeed, a signature win can offer massive payoff to VCs, even if the fund-level returns are modest, and can create enough buzz to sustain new fundraising for a decade or more. We often joke that the venture industry uses lottery slogans with Ivy League veneer: optionality is a fancy word for ”you’ve got to be in it to win it.“ And, indeed, the business is rife with the managers who are “spraying and praying,” but those VCs that are able to deploy some unfair advantage, leverage ecosystems, benefit from experience, or hew to a consistent and thoughtful process can often make their own luck and enjoy more consistent results year-over-year and fund over fund.

Last, authenticity is an important vector of our evaluation. By this term, we don’t mean that we are looking simply for swell folks. Rather, we seek well-aligned robust nonconformists that have the courage of their convictions and demonstrate a consistency between their ideas and their actions. In a business that is plagued by considerable unhealthy egoism, we look for VCs that can demonstrate confident self-awareness. Those who have a keen sense for their own behavioral footprint, awareness of their limitations, and engaging demeanor are often those who can offer the best and most productive catalytic engagement with entrepreneurs as coaches and mentors. Additionally, these managers must be true Partners (with a capital P) to us and thoughtful stewards of the capital with which we entrust them.

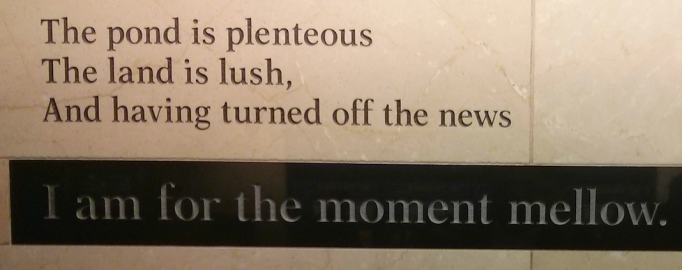

Our task is not an easy one, but today’s advances in technology are truly breathtaking and we believe in what Whitman called, “the genius of the modern, child of the real and ideal.” Our framework described above helps us to organize our talents and energies against the endlessly challenging task of working with people or inventing the future. We could imagine no more humbling and exciting exercise.

So, over the last couple of days I’ve heard a bunch of people here in Silicon Valley talk about how we might abolish the Electoral College. It’s not an unreasonable impulse coming from people for whom Disruption is a religion – and who live in a state that voted two-to-one for Clinton.

So, over the last couple of days I’ve heard a bunch of people here in Silicon Valley talk about how we might abolish the Electoral College. It’s not an unreasonable impulse coming from people for whom Disruption is a religion – and who live in a state that voted two-to-one for Clinton.